100 years of Simavi in retrospect

One hundred years. That's several generations of people who have dedicated themselves to health, equality, and access to clean water. Over the past century, Simavi has transformed from a foundation that provided aid to an organization working towards system change. Because the fight for water, equality, and justice is far from over.

1925-1950: Where it all began

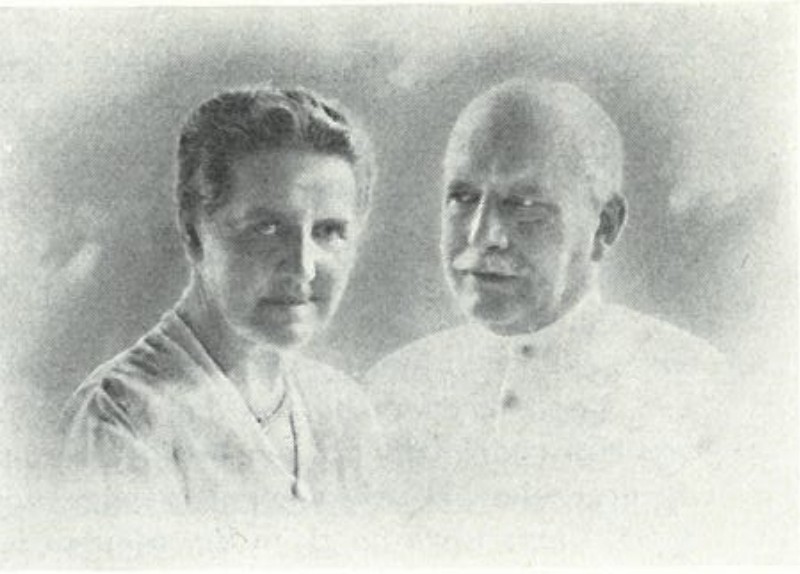

In 1925, an idea emerged that continues to influence lives a hundred years later. Hubertus Bervoets, a former missionary doctor, and his wife Louise Leonore Bervoets-van Ewijck, an experienced nurse, jointly founded the "Foundation for Medical Affairs for Indigenous Peoples" – Simavi.

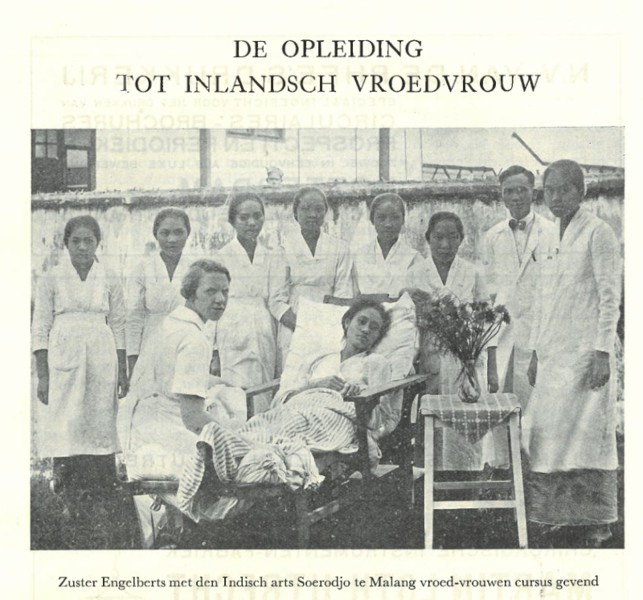

Simavi was born from the realization that medical care in the Dutch colonies was seriously inadequate. The Bervoets couple – with their roots in missionary work, but aware of the drawbacks of missionary rhetoric – wanted to provide practical medical care and train local healthcare providers in Indonesia. Not only Dutch doctors, but especially Indonesian midwives, had to be given their place in the healthcare system.

Yet, this mission was certainly not free from colonial ideas. Simavi's early communications speak of the "spiritual upliftment" of the Javanese population and the need to convert them to Western medicine. Local healing methods were ridiculed, and Western knowledge was seen as superior.

This contradiction—genuine care and simultaneously structural inequality—runs like a thread through Simavi's first decades.

Did you know...

Louise Leonore Bervoets was head nurse at the missionary hospital in Modjowarno and trained local midwives there before Simavi was founded.

She was knighted at the same time as her husband, but her name later disappeared from the official founding story of Simavi.

In 1925 Simavi stated: ‘There must be a complete change in the intellectual life of the Javanese...’ – a sentence that emphasizes the colonial ideology of that time.

1950-1975: Decolonization and the Aid Worker's Blind Spot

During World War II, Simavi remained silent. In 1947, Simavi resumed its activities. The Japanese occupation had ended in 1945, so the Dutch felt they could pick up where they had left off in Indonesia, both in governing and in providing aid.

Even after Indonesia's independence, the perspectives within Simavi often remained colonial. The people receiving aid were now described as "ordinary people," but often with a paternalistic undertone.

Yet, there was also a shift. These decades saw the emergence of the first form of structural development cooperation. It was no longer just about emergency medical aid, but also about the broader context: education, hygiene, and food. In practice, Simavi continued to primarily supply medical supplies and resources to Dutch doctors abroad, but the tone began to shift.

It would take decades for Simavi to chart its current course. But in this time of transition, something important became clear: the world is changing, and organizations like Simavi cannot afford to lag behind. In the quiet awakening of decolonial thinking, in the realization that aid is not always innocent, lies the beginning of a different approach.

Did you know...

During this period, Simavi campaigned with poster texts such as: ‘The Simavi boat: floating hospital for the inlands.’

In 1972, Simavi changed the meaning of its name from ‘For Indigenous Peoples’ to ‘Venezuela to Indochina’, as the organization no longer works solely in the former colonies.

In the early 1970s, Simavi was one of the first and oldest development organizations to establish an important advisory body on development cooperation for the Dutch government.

1975-2000: From collection box to healthcare system

In 1975, Simavi's fiftieth anniversary, everything was changing. The tropical doctor gave way to the community health worker. Help became less about what you bring and more about what you build together.

Increasingly, the message was that health starts locally. In the villages, with women, with clean water. In the Netherlands, Simavi's image was also changing. The organization grew rapidly: from a budget of 1.8 million guilders in 1972 to over three million in 1976. Television and radio spots, school screenings, collection boxes, postcards, and children's books were added.

During this period, the first clear priorities emerged that still characterize Simavi's work today: water and women. In 1989, a major campaign focused on maternal and child care was launched. In 1992, everything revolved around drinking water, with the slogan: "Clean water, essential."

Doctors and engineers contributed to projects and fundraising. The organization professionalized—and simultaneously realized: a pump is only useful if people know how to maintain it. The world was changing. And Simavi was moving with it.

Did you know...

In 1987, ‘drinking water supply’ was the main theme of Simavi’s work – with more than 2,500 boreholes dug in India.

The Simavi choir performed in churches and community centres during the collection week and made its own record that you could buy.

Simavi's name was reinterpreted in Latin: ‘Succurrens In Mundo Afflictis Viribus Iunctis’ – loosely translated: ‘United efforts to help the sick in the world.’

2000-2025: Water, Women, and the Power of Local Change

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Simavi once again finds itself at a crossroads. The collection box and the well-known tropical doctor are disappearing, and the number of private donors is declining. What remains is the mission: health. What changes is who decides how to get there.

Local partners, female leaders, village organizations – they are increasingly taking the initiative. Simavi supports, advises, and finances, but no longer dictates what needs to be done. In the early 2000s, "water" becomes the key word, and more importantly: who provides it, who suffers from the shortage, who lacks agency?

The answer is always the same: women. They fetch the water. They miss school or work if there is no toilet. They become ill, unsafe, or invisible if sanitary facilities are lacking.

Since the 2010s, Simavi has increasingly worked in alliances. These are strategic collaborations, aimed at system change. Shifting the Power becomes a guiding principle.

Simavi recognized that drinking water supplies and sanitation are inextricably linked to the impacts of climate change. Climate change was already a prominent issue on the agenda in 2006. In 2023, Simavi launched the "Stop Sex for Water" petition. Climate change is worsening access to water and leading to women and girls being pressured to have sex in exchange for water. The petition ultimately collected more than 70,000 signatures, which were presented to the Dutch House of Representatives and the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Water and Sanitation.

Did you know...

In 1994, Simavi still worked in more than 30 countries simultaneously – but in the 2010s the number was reduced to 6 to 8 focus countries.

Simavi was the first NGO member of the Netherlands Water Partnership and set up an NGO platform there that also influenced government policy.

In 2006, Simavi was invited to the Dutch premiere of An Inconvenient Truth, where the organization was one of the first to make the connection between climate change and water justice.

2025-: The next 100 years start now

One hundred years of history means one hundred years of learning, listening, and changing. It means acknowledging when we were wrong, celebrating the progress we made, and asking again and again: what is just, and who decides?

We know one thing for sure: the challenges of the coming century demand more than good intentions. The climate crisis threatens access to clean water, to food, to security. Inequality is growing. And the people hardest hit are still too often excluded from power and resources.

From 22 March 2026 – World Water Day – Simavi will continue this work as a member of the WaterAid family, a global not-for-profit working to provide clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene for everyone. Simavi will therefore become WaterAid Netherlands. This way, we can increase our impact while still working towards the same mission: water justice for all.

Because we don't know what the world will look like in a hundred years. But we do know this:

Justice demands perseverance. And allies.

Thank you for being one.

Three starting points for the future

Water and a toilet for all

Clean drinking water, a safe toilet, and good hygiene. We believe everyone should have access to these. That's why we must join forces worldwide to end the water crisis.

Local climate solutions

The consequences of the climate crisis are being felt everywhere. Vulnerable communities must be empowered to work on climate-resilient solutions. That's why we continue to push for better climate and water financing.

A stronger position for women

The unequal position of women and girls means that solving the water crisis isn't given sufficient priority. That's why we continue to invest in their strength, their networks, and their leadership.

Do you want to know more about Simavi's history?

Download our jubilee booklet (only available in Dutch)